|

Fig. A: Laboratory demonstration of the ice formation. The container on the left side of the photo has a stratified fluid

with pink corresponding to the heaviest fluid, clear/ice the lightest and the blue has an intermediate density. The

container on the right side of the photo corresponds to an un-stratified one density fluid throughout. Both containers

were placed in the freezer (in a manner that allowed them to be cooled only from the top) for the same amount of time.

Ice is only visible in the left (stratified) container because the stratification prevented convection. Avoidance of

convection permits ice to form on top of the stratified fluid much faster than it would in the homogeneous non-stratified

fluid on the right, simply because, in the stratified case, there is much less fluid to cool down. The container on the

left represents the "springs ice" (i.e., the region above the plume generated by the springs) whereas the container on the

right represents the remaining unfrozen part of the lake.

Fig. A: Laboratory demonstration of the ice formation. The container on the left side of the photo has a stratified fluid

with pink corresponding to the heaviest fluid, clear/ice the lightest and the blue has an intermediate density. The

container on the right side of the photo corresponds to an un-stratified one density fluid throughout. Both containers

were placed in the freezer (in a manner that allowed them to be cooled only from the top) for the same amount of time.

Ice is only visible in the left (stratified) container because the stratification prevented convection. Avoidance of

convection permits ice to form on top of the stratified fluid much faster than it would in the homogeneous non-stratified

fluid on the right, simply because, in the stratified case, there is much less fluid to cool down. The container on the

left represents the "springs ice" (i.e., the region above the plume generated by the springs) whereas the container on the

right represents the remaining unfrozen part of the lake.

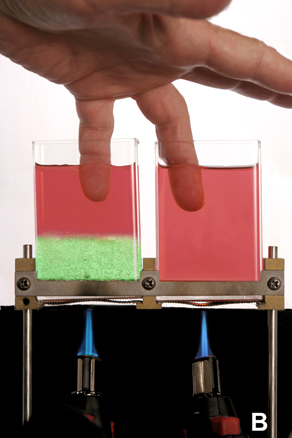

Fig. B: Further illustration of how important stratification is to the cooling and warming of fluids.

Here, we use heating and boiling, as opposed to cooling and freezing shown in Fig. A, to illustrate this point.

The container on the left has two fluids; the green is the heaviest whereas the red is the lightest.

The container on the right has a homogeneous un-stratified fluid. The burners below heated both containers

for the same amount of time. As in the cooling and freezing case shown in Fig. A, the stratification prevents convection.

Thus, the green fluid on the bottom of the left container is boiling while the fluid above it,

as well as the fluid in the other container, are still not boiling. To demonstrate that, indeed,

only the green fluid is boiling, I have placed my fingers in the red fluids. (Don't try this at home!)

This process is the reverse of the "springs ice" formation shown in Fig.A.

Fig. B: Further illustration of how important stratification is to the cooling and warming of fluids.

Here, we use heating and boiling, as opposed to cooling and freezing shown in Fig. A, to illustrate this point.

The container on the left has two fluids; the green is the heaviest whereas the red is the lightest.

The container on the right has a homogeneous un-stratified fluid. The burners below heated both containers

for the same amount of time. As in the cooling and freezing case shown in Fig. A, the stratification prevents convection.

Thus, the green fluid on the bottom of the left container is boiling while the fluid above it,

as well as the fluid in the other container, are still not boiling. To demonstrate that, indeed,

only the green fluid is boiling, I have placed my fingers in the red fluids. (Don't try this at home!)

This process is the reverse of the "springs ice" formation shown in Fig.A.

|

|